Transit on time arrival: explorations from an equity perspective

Arriving late to work or a doctor’s visit because your bus ran late can be more than just a minor inconvenience. Research suggests that certain kinds of employers may discriminate against job candidates who use the bus based on a prejudicial assumption that employees without cars aren’t as reliable. Some doctors screen patients for access to transportation as a ‘social determinant of health,’ because not owning a vehicle can mean patients are more likely to arrive late or miss important health appointments.

Unfortunately, most transportation research evaluates the equity of transit systems using planned agency schedules, and not how well buses, trains and streetcars actually adhere to those schedules. In some neighbourhoods, this is not a big deal: at a busy stop that has a new bus coming every 10 minutes, one of those buses being 5 minutes late or a couple minutes early doesn’t matter as much because another one is coming shortly behind it. But on an infrequent route that comes every 20 minutes or more, a delayed bus or an early bus can mean missing a connection and being late to important activities.

Transit app’s Rider Happiness Benchmarking (RHB) survey asked more than 26,000 app users in the U.S. and Canada how certain they feel that they are able to arrive on time. Transit app, a Mobilizing Justice partner, provides real time bus arrival times and crowding information, making the survey a unique source of information on bus riders’ experiences and views. The October 2021 edition of the quarterly survey asked app users how strongly they agree that they are “able to arrive on time” using transit, with possible answers ranging from 5-strongly agree to 1-strongly disagree. We collapsed this into an indicator variable where those who agreed or strongly agreed are a “Yes” answer regarding arriving on time, and all other responses are a no. This post explores demographic and geographic differences in the percent of yeses categorized in this way.

Whose transit arrives on time?

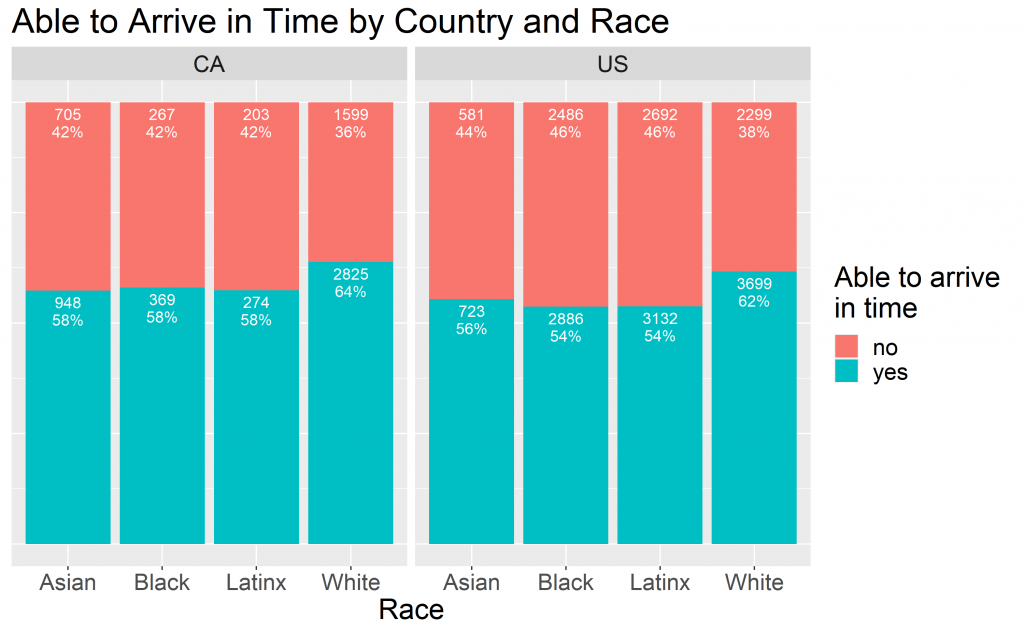

Canadian respondents are slightly more likely than Americans to report being able to arrive on time, at 60% versus 56% respectively. In both countries, however, white residents are more likely to report being able to arrive on time, as demonstrated in Figure 1 below. While 64% of White respondents in Canada believe they are able to arrive on time using transit, only 58% of racialized respondents say the same, and this difference is statistically significant according to chi-squared and t-tests.

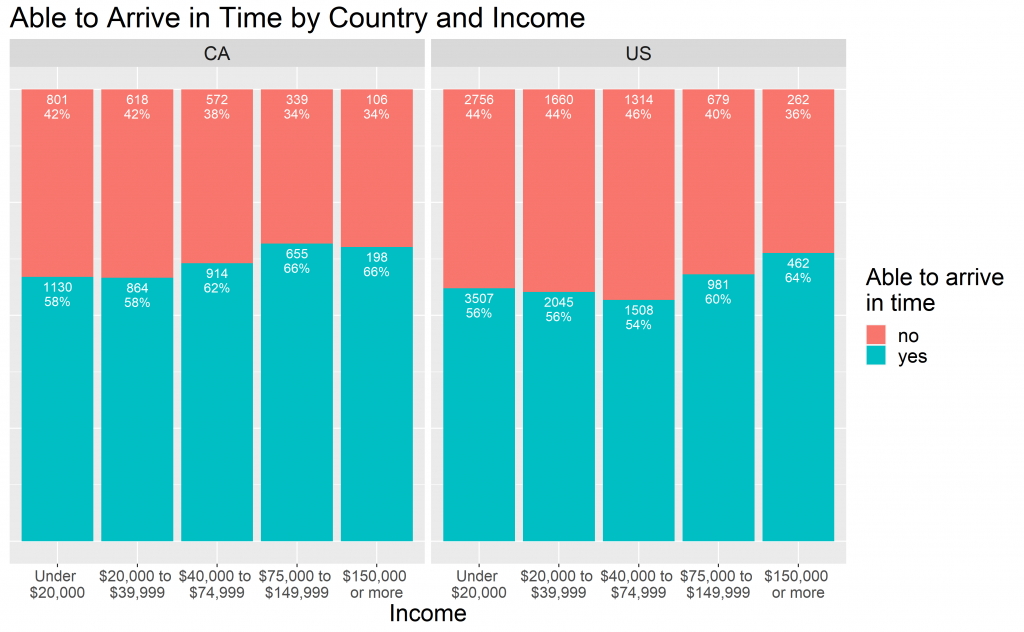

Similarly, riders with higher incomes in both countries are more likely to report being able to arrive on time compared to riders on lower incomes. At the high end of the income spectrum, 66% of Canadian riders report arriving on time, versus 58% of respondents at the lower end.

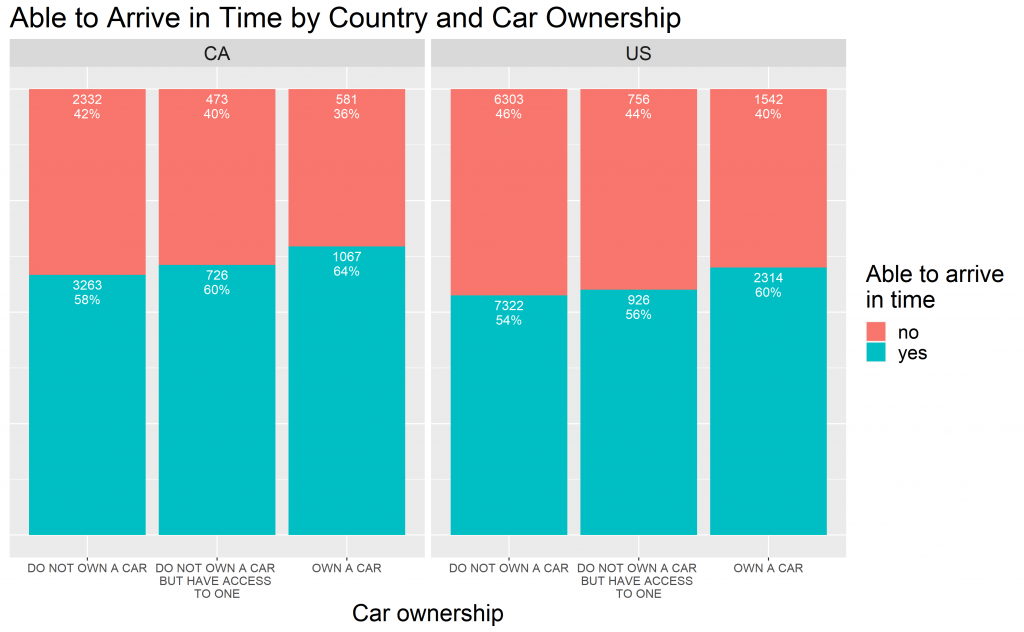

Finally, the data reveal a correlation between vehicle access and perceived on time arrivals of transit. In Canada, 64% of vehicle owners who responded to the survey report being able to arrive on time using transit, compared to just 58% of those with no vehicle access. Respondents who had access to, but did not own, a vehicle, fell in between, at 60%. This could reflect that riders who own a car may be avoiding less reliable routes when they wish to, a choice that is not necessarily afforded to riders who do not have access to a car.

Overall, this analysis suggests that not everyone’s transit is equally likely to arrive on time, and that disparities in transit performance in Canada may fall along lines of race, income, and vehicle ownership. We know that wealthier transit users are more likely to use subways and commuter rail, compared to lower-income riders who often need to take longer bus rides, and this modal difference may explain the patterns we have found as most of Canada’s buses operate in mixed traffic. But because the survey used in this analysis is limited to people who used the Transit app in October 2021, we cannot definitely claim this is true. Regardless, the sample is unique due to its large size and international scope, and it allows us to conclude that equity assessments of transit performance warrant further investigation using representative data. In the United States, such efforts are codified into government regulation based on the Federal Transit Administration’s interpretation of the U.S. Civil Rights Act. Transit agencies must prove there are no disparate impacts along lines of race and income. However, similar analyses are uncommon in Canada.

Several Mobilizing Justice affiliated researchers have begun to conduct such assessments, including on bus on-time performance, subway disruptions, and transit delays. To learn more about transit performance research, visit the Transit Analytics Lab at the University of Toronto, led by MJ co-applicant Professor Amer Shalaby.

You may also like

Removing Fare Barriers: Free Public Transit for Youth Experiencing Homelessness in Toronto

Removing Fare Barriers: Free Public Transit for Youth Experiencing Homelessness in Toronto

Noah Kelly is the Director of Research & Partnerships at the Transit Access Project (TAP) and has recently completed his Master of Arts at McGill… Read More

The Hidden Price of Clean Transportation

The Hidden Price of Clean Transportation

Lessons from the Transition to Electric School Buses The French version of this blog post is available HERE. Canada’s 51,000 school buses… Read More

Youth Experiences with Active Transportation in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada

Youth Experiences with Active Transportation in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada

About the Prioritizing Populations Study Group My name is Alexandra Sbrocchi, and I am a rural planner and third-year PhD candidate in the School of… Read More