The Hidden Price of Clean Transportation

Lessons from the Transition to Electric School Buses

The French version of this blog post is available HERE.

Canada’s 51,000 school buses carry 2.2 million children daily, making them one of the largest public fleets in the country. For decades, those buses have been diesel-powered, exposing students to harmful emissions linked to asthma and other health risks – impacts that fall more heavily on some communities than others. Electric school buses therefore promise cleaner air and quieter rides, making them a clear win for children’s health and national climate goals.

However, when we look beyond the tailpipe, the transition to electric school buses becomes more complicated. The batteries that power electric vehicles, including electric school buses, rely on minerals like nickel, cobalt, and lithium. Extracting these resources raises profound equity questions: Who bears the environmental and social costs of mining? Who benefits from electrification? And how do we ensure Canada’s transition doesn’t deepen existing inequities?

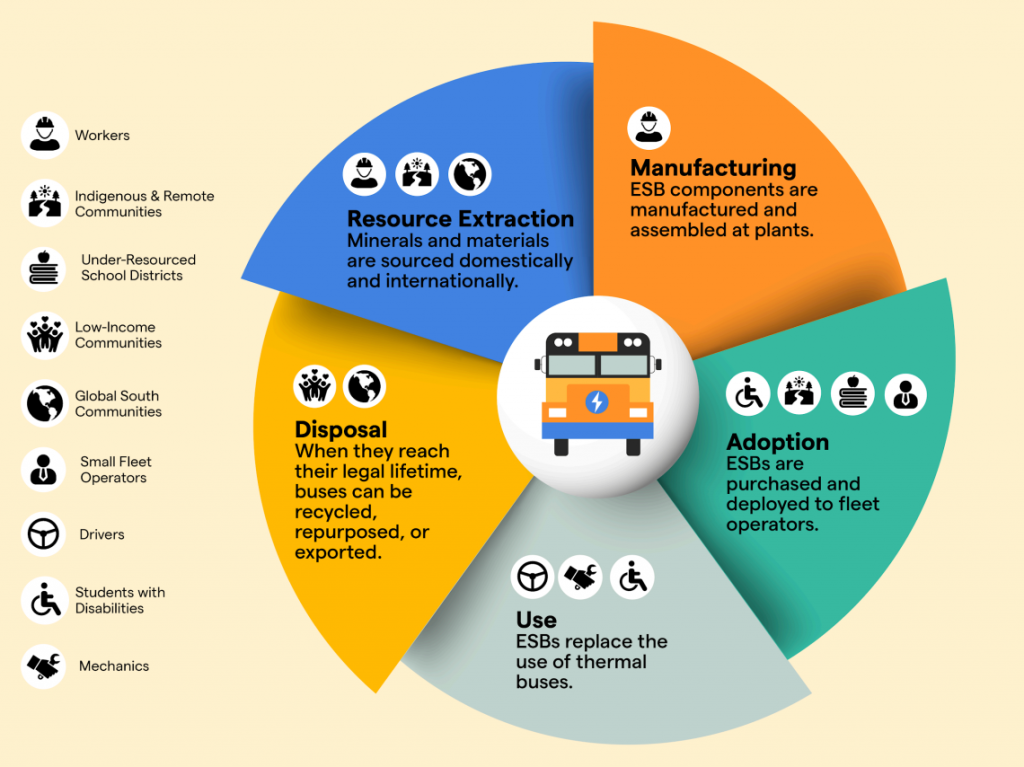

Figure 1. Overview of the Electric School Bus Lifecycle.

Source: Canadian Electric School Bus Alliance (2025).

These questions prompted the Canadian Electric School Bus Alliance (CESBA), led by Green Communities Canada, to publish its recent report, “Embedding Equity in Canada’s Transition to Electric School Buses“. Its work shows that while electrification offers undeniable benefits, it also risks perpetuating patterns of harm, especially for Indigenous communities.

Indigenous Lands: The Foundation of the EV Transition

Across Canada, mining for battery minerals often occurs on or near Indigenous lands. In fact, 85% of the world’s lithium reserves are located on or near Indigenous lands. While essential for electric vehicles, resource extraction projects frequently disrupt ecosystems, contaminate waterways, and strain community well-being, as seen in the Mount Polley disaster. Too often, they also proceed with little to no consultation, leaving Indigenous communities to shoulder disproportionate impacts.

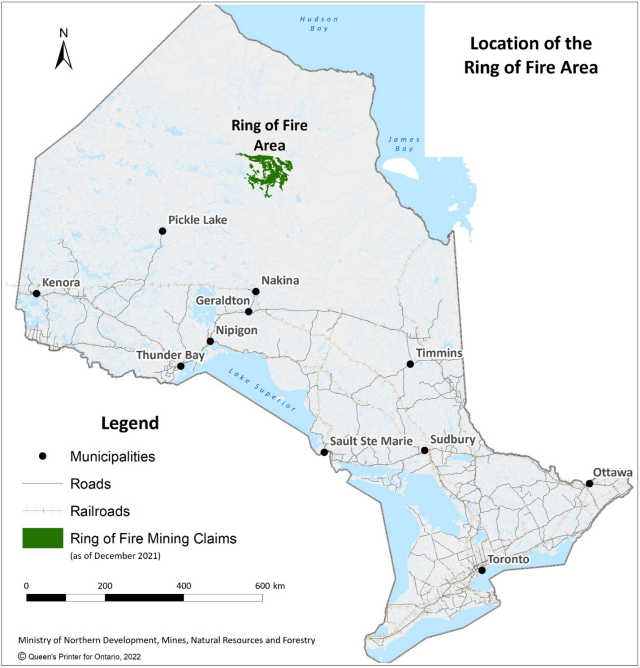

Ontario offers a stark example. The provincial government recently passed Bill 5, creating “Special Economic Zones” where mining projects can bypass regulations, including environmental protections. The first targeted zone is the Ring of Fire, located in Treaty No. 9 territory in Northern Ontario. The region is rich in minerals needed for electric vehicle batteries, but it’s also home to wetlands that store large amounts of carbon, rivers that sustain life, and communities whose rights are at risk of being sidelined.

With these hidden costs in mind, to what extent will these communities benefit from electric vehicles built using minerals extracted from their territories?

Figure 2. Location of the Ring of Fire Area.

Source: Ontario (2022).

Case Study: Electric School Buses

Our research found that, when it comes to electric school buses, Indigenous communities often bear the negative impacts of resource extraction, but rarely share in the benefits of electrification. Jurisdictions with large Indigenous populations—Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Nunavut, Northwest Territories, and Yukon—lack electric school buses.

Figure 3. Number of Electric School Buses per Canadian Jurisdiction.

| Jurisdiction | Number of Electric School Buses | Total School Bus Fleet |

| British Columbia | 158 | 3,166 |

| Alberta | 6 | 7,114 |

| Saskatchewan | 1 | 3,083 |

| Manitoba | 0 | 2,546 |

| Ontario | 25 | 20,833 |

| Quebec | 1,606 | 10,650 |

| New Brunswick | 22 | 1,234 |

| Prince Edward Island | 107 | 323 |

| Nova Scotia | 0 | 1,459 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1 | 1,009 |

| Yukon | 0 | 60 |

| Northwest Territories | 0 | 73 |

| Nunavut | 0 | 120 |

| Canada | 1,926 | 51,670 |

Source: The number of electric school buses is estimated because no comprehensive data source is available. Total fleet numbers are from Transport Canada (2020).

Charging infrastructure gaps, higher baseline transportation costs, and limited government funding can explain, in part, these inequities in electric school bus availability. These barriers are not unavoidable: they stem from policy choices that shape where resources flow and who benefits.

What Needs to Change

To ensure Canada’s transition to electric school buses doesn’t exacerbate existing inequities, we need stronger safeguards and more inclusive policies surrounding mining and electrification:

- Reinforce environmental and social protections in resource extraction, with amendments to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act requiring environmental justice impact assessments for all projects.

- Embed meaningful consent in federal review processes and uphold Indigenous rights to refuse projects.

- Mandate Community Benefits Agreements under the Impact Assessment Act to secure fair outcomes for local communities throughout the mining lifecycle.

- Expand targeted federal funding to increase Indigenous access to electric school buses, ensuring that those most affected by resource extraction also share in the benefits of electrification.

Clean transportation shouldn’t come at the expense of Indigenous lands and communities. Canada’s electric school bus transition can deliver health and climate benefits, but only if equity is at its core. As this shift unfolds, we’re invited to ask: how can clean transitions truly serve all communities, not just some?

You may also like

Removing Fare Barriers: Free Public Transit for Youth Experiencing Homelessness in Toronto

Removing Fare Barriers: Free Public Transit for Youth Experiencing Homelessness in Toronto

Noah Kelly is the Director of Research & Partnerships at the Transit Access Project (TAP) and has recently completed his Master of Arts at McGill… Read More

Youth Experiences with Active Transportation in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada

Youth Experiences with Active Transportation in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada

About the Prioritizing Populations Study Group My name is Alexandra Sbrocchi, and I am a rural planner and third-year PhD candidate in the School of… Read More

Documenting Canada’s Community Response to Transport Poverty: A 5-Year Review

Documenting Canada’s Community Response to Transport Poverty: A 5-Year Review

With the recent release of the Canadian Community Initiatives Addressing Transport Poverty Catalogue, accompanying report, and interactive web map, a multi-year effort… Read More