Findings from the City of Grand Rapids’ Shared Micromobility Free Fare Pilot Program

The Free Fare Pilot

Shared micromobility systems, such as bikeshare and scootershare, are increasingly important to cities’ transportation strategies, as they seek to move away from car dependence. The dramatic growth of shared micromobility systems, in both prevalence and popularity, underscores the importance of weaving equity considerations into the development of shared micromobility. Transport policy on shared micromobility is also a key way that policymakers can influence micromobility use in general.

A study of 239 shared micromobility programs in the U.S. found that 62% adopted some form of equity requirement, with 32% implementing a reduced fare program. Such programs are vital for transport justice, ensuring that as mobility systems are implemented, their benefits are distributed equitably.

Our study investigated the effects of a free fare pilot program offered by the City of Grand Rapids and Lime, a major micromobility operator, building on the existing Lime Access program that provides reduced fares to low-income residents in many cities globally. In the summer of 2024, the pilot program provided five free 30-minute rides per day to qualifying residents, resulting in 1124 Access participants taking 35,000 trips.

We studied the pilot using trip data, surveys, and interviews with participants, to understand how the program influenced travel patterns, affected participants’ lives, and contributed to advancing transport equity.

Participants of the free fare program use micromobility differently.

Access riders behave differently than non-Access riders, especially when cost is removed.

Trip data reveals stark contrasts:

- Trip duration: Before the pilot, Access riders averaged 10 minutes; non-Access riders, 18 minutes. During the pilot, both averaged 16 minutes. After the pilot, Access riders dropped to 10 minutes, non-Access to 13 minutes, highlighting cost sensitivity among low-income users.

- Temporal differences: Non-Access trips peak on weekends, suggesting that there are more recreational trips with this group, possibly owing to tourists and other non-residents using the system. This echoes another study of subsidized fares of shared micromobility systems, which found more utilitarian trips among subsidized rides.

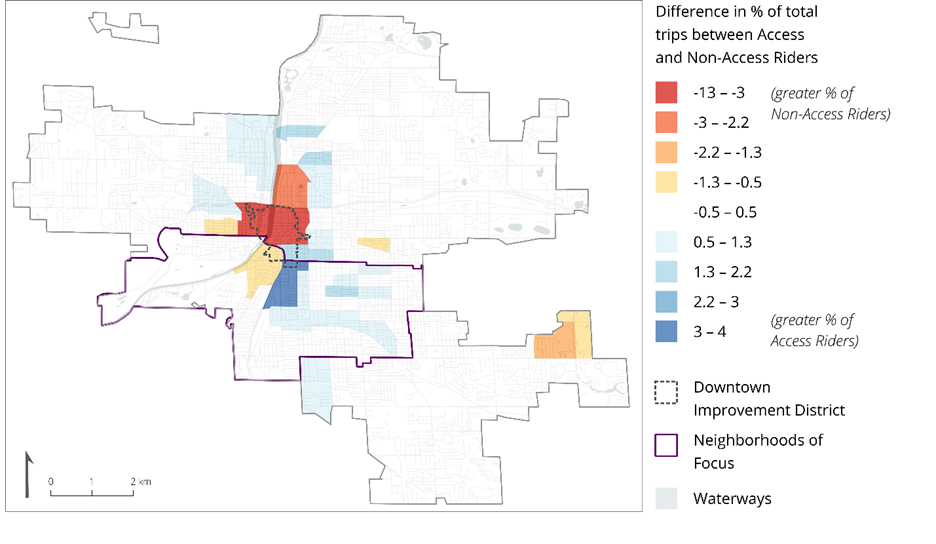

- Spatial Patterns: We looked at differences in spatial patterns, through the percentage of total trips made by Access riders and non-Access riders that start or end their trips in each area during the pilot. Though both groups’ trips were concentrated in the downtown area, Access riders’ trips were more dispersed overall. Grand Rapids’ “Neighborhoods of Focus“, characterized by higher poverty, unemployment, and lower educational attainment, see proportionally more ridership from Access riders, where 55% of Access trips are located, compared to 55% of non-Access trips.

Participants use shared micromobility significantly more with free, rather than 50% Off.

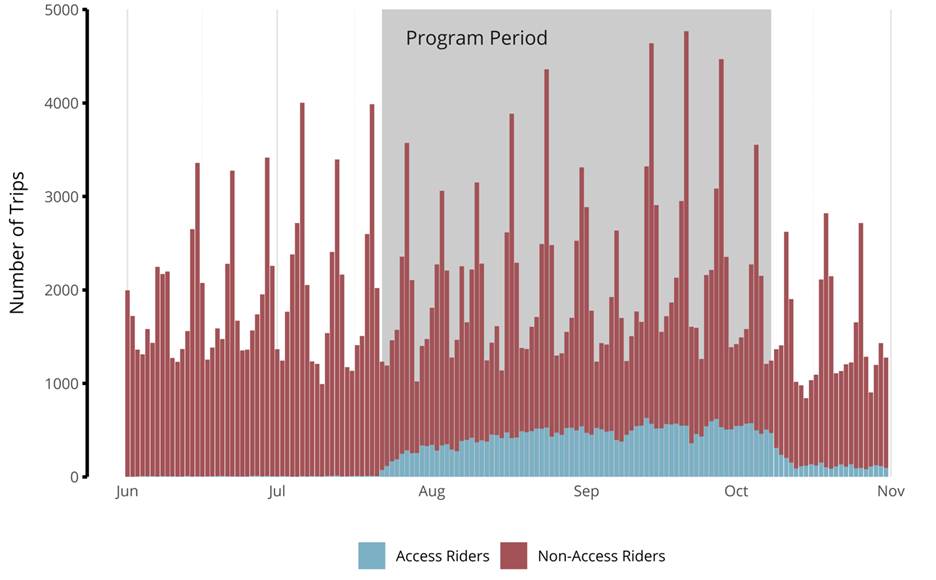

By comparing the trip data of Access riders before, during, and after the pilot program, we found that there is a significant difference between free fares and 50% Off fares.

Before the pilot, when Access riders had 50% off fares, just 1% of total trips were Access trips. During the free fare program, 18% of trips were Access trips, and following the pilot, when the 50% fares returned, the proportion of discounted trips fell to 8%. The poverty rate of Grand Rapids is 18% – so, during the pilot, the proportion of free trips matched the proportion of the population experiencing poverty.

Through a statistical (differences-in-differences) analysis, we found that Access riders took an average of three more trips per week than non-Access riders during, compared to before, the pilot.

Beyond the clear effect of free fares, these figures also suggest that awareness is a key barrier to the uptake and success of equity programs. It is also possible that people who used shared micromobility during the free ride pilot were convinced by its utility and continued to use the system after the program, as a result of their experience.

Participants use the system for a range of purposes and experience exceptional benefits from their improved mobility.

We asked survey respondents, Access users, about their use of the system, and found that 67% used the vehicles for commuting or work-related travel and 63% for shopping-related travel. Interviewees told us about using the system to search for jobs and attend new educational programs, and were worried that with the program ending, they would lose their access. One interviewee spoke of using the service to find employment while living in a homeless shelter, saying: “literally, you guys [ Lime] gave me a job“.

We also found that 62% for social travel or attending events and 65% for recreational travel. We heard about using the shared system to attend social gatherings, community organizations, such as “fathers’ groups” and parent-teacher associations, and community events. Interviewees also spoke of being able to explore the city, its cultural institutions, green spaces, and public places.

Participants feel strong gratitude and appreciation towards the city and micromobility operator.

When we asked about feelings towards micromobility and the shared system, 93% reported increased support for the shared program, and interviewees discussed possibly purchasing their own micromobility vehicles for future use, following their experience.

Interviewees very strongly expressed their feelings of gratitude and appreciation for the city and the micromobility operator: “it [the free fare program] shows that the city cares about us“. There was a reported sense that the program was evidence of investment in “the community”, and people spoke of reciprocal pride in the city, partly owing to their experiences exploring the city through the program.

Participants feel a sense of freedom from their improved mobility.

We heard from several interviewees about feeling a sense of freedom from their improved mobility. Or, conversely, the feeling of being “trapped” without access to the free fares. One interviewee said the program was good for her mental health, motivating her to leave her windowless apartment and experience the city. Another, at the time living in low-income housing, told us that the program helped her look for work and get to medical appointments, but also helped her get out more, socialize, and deal with her social anxiety.

Yet another interviewee said: “What it did is it gave me the feeling that I’m not trapped, if that makes sense. I’m not in a point where I’m, you know, trapped in the house and not able to go and do anything to not be able to, you know, go and see anything. I was able to see a lot more of Grand Rapids than I ever had been able to.“

Mobility has often been associated with freedom. Our interviewees attest to this, where their improved access to shared micromobility was experienced as feeling free. “Freedom” is more that a question of time and money: it’s ultimately emotional, and clearly something resonant with the interviewees.

Looking forward: Free rides, freedom

Shared micromobility systems can form part of the urban fabric, but without fare subsidy programs, low-income residents may be excluded from their use. In effect, then, these systems become two: one for those who can afford them, and one for those who cannot.

We found that fare subsidy programs are effective in encouraging use by low-income residents and have transformational effects on those that take advantage of the opportunity. The pilot program saw success in encouraging the equitable use of micromobility, but since a goal of fare subsidy programs is also to encourage behavioural change – mode shift, access to employment, and so on – it is important that such programs are implemented over the long-term to support more substantial life changes.

The freedom of mobility can be considered a human right and part of the right to the city. Fare subsidy programs can be a key part of guaranteeing this right. We found evidence of the importance of the program to low-income residents, and the value of freedom through mobility.

About the study

This study was conducted by a team of researchers: Daniel Romm, PhD candidate, McGill University Department of Geography; Fajle Rabbi Ashik, PhD student, McGill University Department of Geography; Calvin Thigpen, Lime; Kevin Manaugh, Associate Professor, McGill University Department of Geography and Bieler School of Environment; Grant McKenzie, Associate Professor, McGill University Department of Geography. The researchers would like to thank the City of Grand Rapids and Lime for running the pilot program and for their support in the evaluation, as well as the study participants who answered surveys and were interviewed.

You may also like

Removing Fare Barriers: Free Public Transit for Youth Experiencing Homelessness in Toronto

Removing Fare Barriers: Free Public Transit for Youth Experiencing Homelessness in Toronto

Noah Kelly is the Director of Research & Partnerships at the Transit Access Project (TAP) and has recently completed his Master of Arts at McGill… Read More

The Hidden Price of Clean Transportation

The Hidden Price of Clean Transportation

Lessons from the Transition to Electric School Buses The French version of this blog post is available HERE. Canada’s 51,000 school buses… Read More

Youth Experiences with Active Transportation in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada

Youth Experiences with Active Transportation in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada

About the Prioritizing Populations Study Group My name is Alexandra Sbrocchi, and I am a rural planner and third-year PhD candidate in the School of… Read More