Removing Fare Barriers: Free Public Transit for Youth Experiencing Homelessness in Toronto

Noah Kelly is the Director of Research & Partnerships at the Transit Access Project (TAP) and has recently completed his Master of Arts at McGill University’s Department of Geography. Noah’s research focuses on how transportation poverty impacts quality of life and the rehousing process for people experiencing homelessness in Toronto.

Mobility is an often-overlooked part of the rehousing process for people experiencing homelessness. In Toronto, public transit is the most common form of non-walking transportation, yet many people experiencing homelessness cannot afford transit fares. As a result, access to essential destinations such as healthcare, supportive services, employment, social supports, and housing opportunities, is often limited or lost altogether. To reach essential destinations, people experiencing homelessness are left with little choice but to use transit without paying, risking fines and conflict with transit authorities. Previous research by Transit Access Project (TAP) has shown that shelters and support services (e.g. shelters, drop-ins, supportive housing providers) in Toronto lack sufficient funding to consistently meet clients’ transportation needs.

Access to sufficient transportation is especially critical for youth experiencing homelessness to maintain support, quality of life, and access essential destinations required in the rehousing process. Research shows that the longer a young person’s first experience of homelessness lasts, the more likely they are to experience chronic or recurring homelessness throughout their lifetime. Removing transportation barriers to access services that aid in rapid rehousing is thus essential in preventing chronic or recurring homelessness among youth.

To address this gap in transportation access, Canadian cities like Edmonton, Calgary, and Guelph, have introduced free public transit programs for people experiencing poverty or homelessness. The City of Edmonton was the first, launching the PATH program in 2016 to offer fully subsidized monthly transit passes as a part of their rehousing case plan. Though these programs exist, there is very little research exploring the impact of affordability-based interventions on quality of life and access to essential destinations required in the process of rehousing.

To fill this research gap, the Transit Access Project (TAP) partnered with Mobilizing Justice and the City of Toronto’s Poverty Reduction Strategy Office to conduct a three-month free public transit intervention at three youth shelters in Toronto. This study answered the following questions: 1) How does the cost of public transit fares act as a barrier to accessing transportation for youth experiencing homelessness in Toronto? 2) If youth do experience transportation deprivation, how does this experience impact their quality of life and access to essential destinations? And 3) How does the provision of free public transit change access to essential destinations and quality of life for youth experiencing homelessness in Toronto?

The study included 36 participants aged 16-25 (mean age 21.5), including 16 men, 13 women, and 7 trans or nonbinary participants. Participants were either living in (n = 28) or recently rehoused from (n = 8) three youth shelters in Toronto. This study used a mix of pre- and post-intervention group interviews, and a longitudinal survey was distributed upon recruitment pre-intervention and at the start, mid, and end points of the intervention. The findings report all the responses received to each survey question. Response rate varied by question, leading the total respondent population to differ between questions.

KEY FINDINGS

Research Question 1: How did the cost of public transit fares act as a barrier to accessing transportation for youth experiencing homelessness in Toronto?

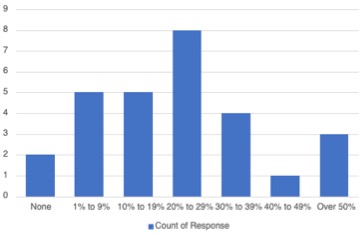

This lack of access led to significant deleterious effects on participants’ quality of life. Participants experienced social, spatial, and economic alienation. Participants lost jobs, missed school, missed medical appointments, lost access to supportive services, experienced social isolation, food insecurity, and emotional distress. This led to overall negative impacts on participants’ material and emotional wellbeing. Before receiving the free transit pass, the cost of public transit was a significant financial burden and barrier to accessing essential destinations for participants. 21 of 28 survey respondents spent more than 10% of their monthly income on transit, with 8 participants spending 30% or more of their monthly income on transportation (see Figure 1). The availability of transportation-specific supports (e.g. single-fare tickets, Uber/Lyft rides, taxi chits) were variable between each of the three shelters and were not sufficient in providing reliable access to essential destinations.

Figure 1. Percentage of Participants’ Income Spent on Transit (n = 28)

Research Question 2: How did transportation poverty impact participants’ quality of life and access to essential destinations?

The cost of public transit was a significant barrier to accessing essential destinations, such as employment, housing opportunities, supportive services, social supports, and food security programs. Youth expressed that their inability to access essential destinations negatively impacted their health, social inclusion, income, feelings of safety, education, financial security, and ability to engage with support services. 24 of 29 survey respondents reported struggling to access essential destinations due to the cost of transit (see Figure 2). The cost of fare was cited as a barrier to work by half of participants, leading to missing job interviews and employment opportunities. Nearly half of participants could not access healthcare due to the cost of transit. Participants with chronic health conditions regularly missed medical appointments due to the cost of transit.

Figure 2. Destinations Participants Struggle to Access Pre-Intervention (n = 29)

Social isolation due to the cost of travel was common amongst participants. 19 of 29 (66%) survey respondents could not visit family or friends due to transit costs, reducing critical support networks that can aid in the process of rehousing (see Figure 2). Participants often had to forgo buying food to afford transit fares to reach critical destinations. Participants struggled to access available food security programs due to the cost of transit.

Research Question 3: How did the provision of free public transit change access to essential destinations and quality of life for youth experiencing homelessness in Toronto?

While receiving the free monthly transit passes, participants reported greater access to support services, employment, housing opportunities, healthcare, social support, recreational spaces, and education. The mean and median monthly income of participants increased overall throughout the intervention. Median monthly income range increased from $250–$549 to $700–$849 and the approximate mean increased from $475 to $695.45. Participants were able to apply to jobs and attend interviews they previously could not reach, helping to secure new employment. Others were able to change jobs to receive more consistent hours and pay. Aaron[1], who had recently immigrated to Canada, stated:

“It helped me to find a job–I never had a job before, but whenever I could see any place where they were advertising, I could just board public transit and go straight away without thinking about it.”

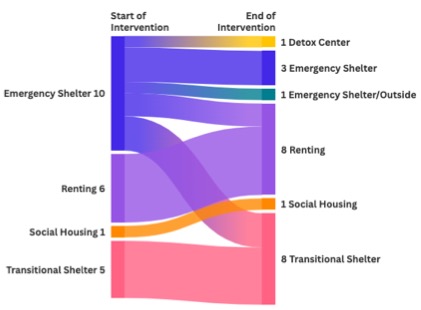

All participants renting or living in a transitional shelter maintained their housing stability throughout the intervention. Five participants successfully moved from emergency housing into private housing or a transitional organization (see Figure 3). Those who moved cited the transit pass as a key factor in accessing housing support and opportunities. Sasha stated:

“It helped me find my first apartment. It helped me save money. I moved out of [the shelter] a few months ago.”

Figure 3. Change in Housing Type Between Start & End of Intervention (n = 22)

Participants’ improved transportation access led to greater engagement with available supports, social networks, and improved their ability to meet their daily needs. These cumulative effects led to overall improvements in quality of life. Participants reported attending more medical appointments, improved mental health and stability, and an increased ability to make plans and execute them to improve their material circumstances. Jayden noted:

“It brought peace of mind. If I got into another hard spot and I needed to go somewhere to find some food or to get groceries, I know I can get there. It’s not only just to see friends. But all my necessities… It really gave me peace of mind.”

Participants’ ability to see friends and family drastically improved during the intervention, enhancing support networks and reducing feelings of loneliness. Angela shared:

“I felt comfortable commuting to [a friend’s] place because I didn’t have to worry about how much I’m spending.”

Final Thoughts

This study showed that the cost of public transit is a significant barrier to support and opportunities for youth experiencing homelessness in Toronto. Providing free public transit significantly improved participants’ access to essential destinations, leading to improvements in quality of life.

Providing free transit is obviously not a fix-all for accelerating the process of rehousing or preventing the degradation of quality of life caused by homelessness. However, lack of sufficient transportation is a significant impediment to a decent quality of life and the process of rehousing, as it impedes access to essential destinations required to become rehoused. The City of Toronto and Toronto Transit Commission should work together to remove the cost of transportation for youth experiencing homelessness. Policing fares for the most marginalized in our community only works to deny access to one’s daily needs and does little to protect revenue, as many youth experiencing homelessness cannot afford transit to begin with. Preventing people experiencing homelessness from riding transit leads to unnecessary hardship and greater friction in the process of rehousing. A longer and larger study should be conducted to observe the impact of this intervention on all age groups and on the rehousing process long-term.

[1] Pseudonyms are used to identify participants.

You may also like

The Hidden Price of Clean Transportation

The Hidden Price of Clean Transportation

Lessons from the Transition to Electric School Buses The French version of this blog post is available HERE. Canada’s 51,000 school buses… Read More

Youth Experiences with Active Transportation in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada

Youth Experiences with Active Transportation in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada

About the Prioritizing Populations Study Group My name is Alexandra Sbrocchi, and I am a rural planner and third-year PhD candidate in the School of… Read More

Documenting Canada’s Community Response to Transport Poverty: A 5-Year Review

Documenting Canada’s Community Response to Transport Poverty: A 5-Year Review

With the recent release of the Canadian Community Initiatives Addressing Transport Poverty Catalogue, accompanying report, and interactive web map, a multi-year effort… Read More