TTC service cuts and transit equity: reflections on a recent report

Tess Peterman is a graduate student with the TransForm Lab at Toronto Metropolitan University.

On March 26th, 2023, the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) implemented Phase 1 of service changes on 20% of their routes to address a major deficit in their operating budget post-pandemic[1]. Most of these changes involve increased wait times in both peak and off-peak hours. At the same time, the transit fare was increased by 10c (excluding for seniors). This means that Toronto residents will now pay more to use a less frequent public transit service.

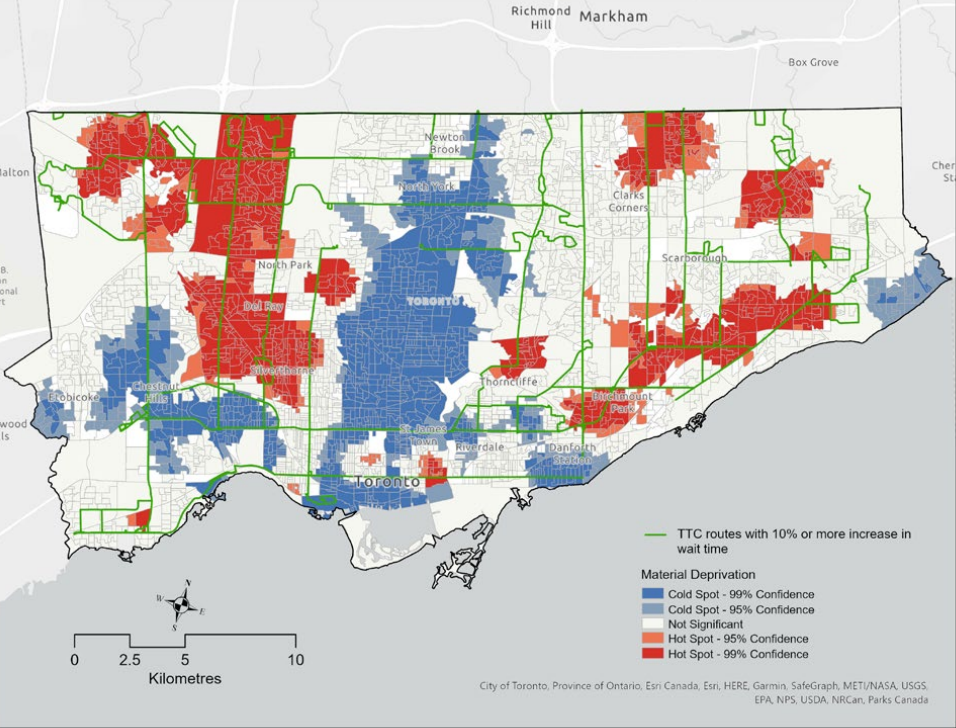

Professor Raktim Mitra and I recently wrote a short report where we mapped the locations of affected routes with the greatest service cuts (28 routes), against the locations of socially and economically marginalized communities within Toronto[2]. Using data from the 2016 Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-Marg), we explored the association between the locations of service reduction, and systematic clusters of dissemination areas (DAs) with high degrees of material deprivation (proxy for concentration of poverty), dependency (proxy for concentration of unemployed population), and ethnic concentration. Our maps showed that:

- 26 of the 28 TTC routes that will experience at least a 10% increase in wait times (93 %) go through or connect to a neighbourhood with high material deprivation;

- 22 of the 28 TTC routes that will experience at least a 10% increase in wait times (79 %) go through or connect to a neighbourhood with high-level dependency; and

- 24 of the 28 TTC routes that will experience at least a 10% increase in wait times (86 %) go through or connect to a neighbourhood with a high level of ethnic concentration.

In comparison, 79% of routes with reduced services went through areas within Toronto with the least material deprivation, 57% of these routes went through areas with the least dependency, and 57% of these routes went through areas with the least ethnic concentration.

Reflection on feedback to the report

The report received significant attention in local media and among public transit advocacy groups. Since then, we received substantial feedback, both positive and negative, which provided us an opportunity to reflect on the value and challenges related to equity-focused transportation analysis. When facing a difficult challenge of balancing public transit operating cost versus revenues related to lower post-pandemic ridership, principles of economic rationalization would suggest that levels of service on the busiest routes and at the busiest times should be maintained, so that fewer people overall are affected by any changes in service. However, in our report, we argue that in an equitable public transportation system, the greatest benefits (or the least lost in benefits) should be offered to socially and economically marginalized communities. In Toronto, these marginalized communities are often located far from the downtown areas and do not generate many transit trips due to various complex reasons, but many in these communities are totally dependent on public transit for their everyday needs. In this context, how do we measure the effects of a public transit service modification? If a few equity deserving people now have to spend more time to get to work, a grocery store, or to visit friends, is that a reasonable compromise compared to the alternative approach where a greater number of transit riders overall would be affected, or is it an unacceptable approach?

Then, there are challenges related to measuring accessibility. Since many marginalized communities are already “transit poor”, relative loss of accessibility as a result of new service cuts would likely be modest, when compared to the effects of similar cuts in other places that are supported by high-frequency public transit. But this small loss in accessibility may trigger a tipping-point and may have life-changing impacts in these communities. How do we address these important equity-concerns when developing various accessibility indices?

To conclude, the recent TTC service changes are a part of a much bigger pattern with more changes proposed to go in effect in May, 2023. In a recent open letter, more than 100 Toronto-area researchers called this a “transit death spiral” and put forward a set of recommendations identifying where additional revenues can be generated to address the TTC operating budget deficit, instead of reducing services[3]. These recommendations should be at the front and centre when transit equity is being discussed during the upcoming Toronto Mayoral race. But researchers should also explore methods of measuring equity-related impacts of public transit, so that these measures can be seamlessly integrated into current transportation planning processes and inform political debate going forward.

Disclaimer: the research described in this piece was not funded by or conducted as part of Mobilizing Justice. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of Mobilizing Justice.

[1] Toronto Transit Commission- TTC. (2023a, February 28). 2023 Service Alignment – Phase 1. Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved from https://ttc-cdn.azureedge.net/-/media/Project/TTC/DevProto/Documents/Home/Public-Meetings/Board/2023/February-28/6_2023_Service_Alignment_Phase_1.pdf?rev=f91163b68acc4f31940bb9d9e727caf4&hash=A6AF38B4B5650B6633B1858C05193897

[2] Mitra, R. & Peterman, T. (2023, March). 2023 TTC Service Changes and Transit Equity in Toronto. Transportation and Land Use Planning Research Laboratory. Retrieved from https://transformlab.torontomu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/TTC-Service-Changes-and-Equity-Report-FINAL.pdf

[3] Klumpenhouwer, W., Palm, M., Farber, S., et al. (2023, February 8). Protect Toronto’s Public Transit from A Ridership Death Spiral: An Open Letter to Federal, Provincial, and Municipal Governments [Open Letter]. Retrieved from bit.ly/open-letter-ttc

You may also like

Removing Fare Barriers: Free Public Transit for Youth Experiencing Homelessness in Toronto

Removing Fare Barriers: Free Public Transit for Youth Experiencing Homelessness in Toronto

Noah Kelly is the Director of Research & Partnerships at the Transit Access Project (TAP) and has recently completed his Master of Arts at McGill… Read More

The Hidden Price of Clean Transportation

The Hidden Price of Clean Transportation

Lessons from the Transition to Electric School Buses The French version of this blog post is available HERE. Canada’s 51,000 school buses… Read More

Youth Experiences with Active Transportation in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada

Youth Experiences with Active Transportation in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada

About the Prioritizing Populations Study Group My name is Alexandra Sbrocchi, and I am a rural planner and third-year PhD candidate in the School of… Read More