Moving towards cycling equity in Toronto: infrastructures, social contexts, and spatial difference

Thomas van Laake, doctoral researcher at the University of Manchester

Introduction

In recent years, equity and justice have become central issues in bicycle planning and advocacy in North American cities. As transportation researchers highlight the unequal spatial distribution of infrastructures, municipal governments have increasingly adopted criteria and methodologies to address these inequities. Equity indicators help identify and locate transportation disadvantages faced by marginalized population groups. A reliance on quantitative analyses and planning criteria, however, may lead some to overlook how differences in socio-spatial contexts across a jurisdiction shape planners’ ability to achieve more equitable outcomes.

Drawing on my doctoral research on Toronto’s bicycle planning processes, in this blog I argue that equitable cycling planning requires spatially differentiated approaches that respond to local conditions and needs. Directing attention to the characteristics of infrastructures and the spatial contexts they operate in, I call for further qualitative attention to the characteristics of infrastructures, differences in urban context, and the needs of local communities to inform the growing interest in measuring and addressing cycling inequalities.

Toronto’s unequal cycling network

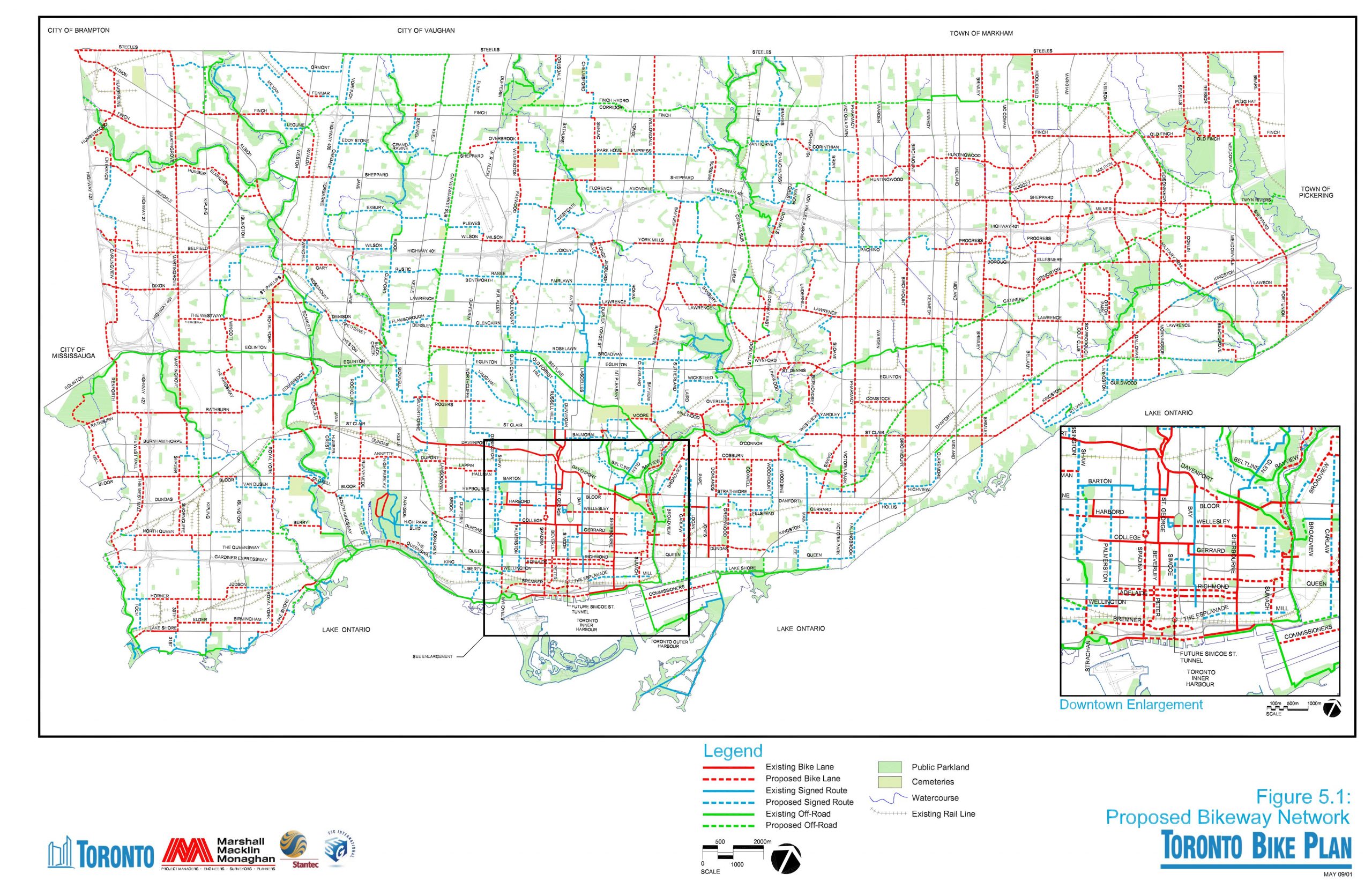

Over two decades after the establishment of an ambitious city-wide cycling network plan in 2001, which aimed to provide equal investment and service provision across the recently amalgamated jurisdiction, Toronto’s cycling network progress is sobering. Despite the availability of a considerable budget and capable institutional apparatus for cycling infrastructure, entrenched local opposition to changes to road configurations largely limited network expansion to recreational facilities.

Figure 1. The 2001 Toronto Bike Plan envisioned a city-wide cycling network with routes along many major suburban arterials. Very few of the suburban routes were implemented in the following decades.

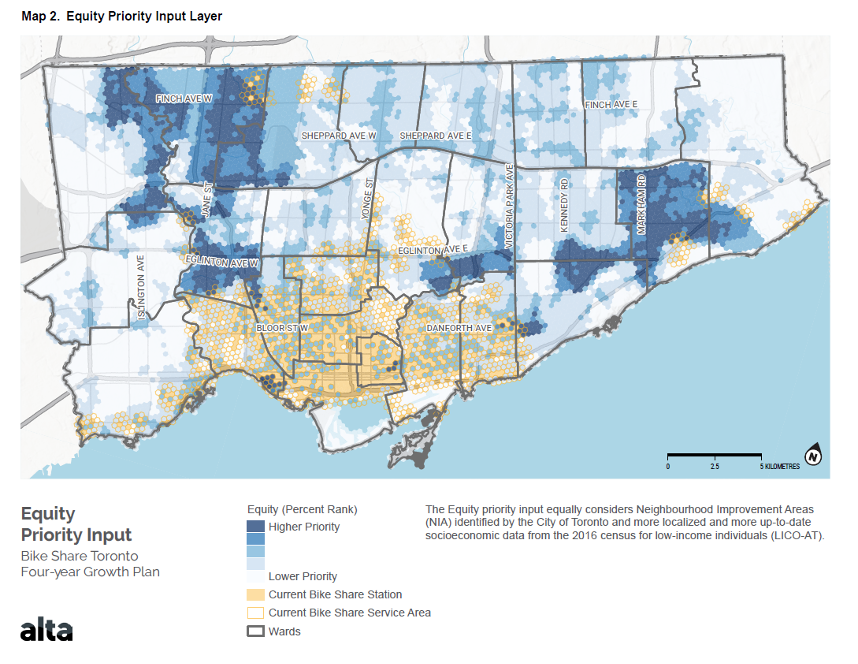

Meanwhile, urban demographic and economic trends have seen lower income and racialized Torontonians displaced from central neighbourhoods into the inner suburbs, where they tend to face considerable transportation disadvantages (Allen & Farber, 2021). Accordingly, transportation equity analyses invariably affirm the need for improved transit and active travel provisions in the suburbs (see Figure 2).

The integration of equity criteria into cycling planning in Toronto from 2019 onwards has centred on the prioritization of Neighbourhood Improvement Areas (NIAs), helping justify interventions in Flemingdon and Thorncliffe Park, two deprived apartment neighbourhoods adjacent to the city centre, as well as improvements in underserved areas around Jane and Finch. Equity criteria have also influenced the siting of new bike share stations in the ongoing city-wide expansion of Bike Share Toronto, with the projected 2025 system coming to serve all but one of the city’s NIAs.

Figure 2. The equity priority analysis in Bike Share Toronto’s 2022 Four Year Growth Plan highlights underserved parts of Etobicoke and Scarborough. (Bike Share Toronto, 2022).

Network expansion strategies

Over two decades on from the 2001 bike plan, Toronto’s planners have never been more committed to implementing cycling infrastructure in suburban wards. With the prioritization of equity complementing the long-standing goal of achieving a city-wide network, TransformTO’s climate mitigation target of 75% of trips to school and work under 5km being walked, biked or by transit has further underlined the need to increase cycling rates in the suburbs.

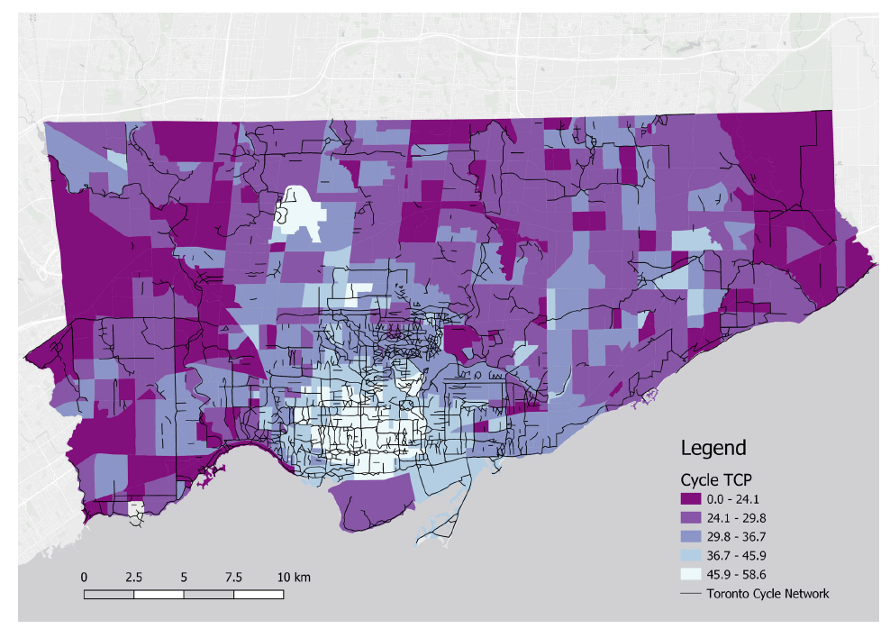

However, these policy goals are not always compatible, not least due to the significant differences in land use and urban form between downtown and suburb. In a study of the Toronto metropolitan area, Raktim Mitra and colleagues (2021) have shown that “all else being equal, urban cycling facilities [are] associated with higher odds of increased commute-related bicycling, compared to suburban locations”. Due to their density and existing cycling network coverage, downtown wards offer much higher destination accessibility by bike (Tabascio et al., 2023; see Figure 3). As Madeleine Bonsma-Fischer and colleagues outline in a recent analysis of strategies for the expansion of Toronto’s cycling network, these spatial differences lead to “trade-offs in spatial coverage, equity, and efficiency” where optimizing for maximum usage will tend to inequitably prioritize facilities in and around downtown.

Certainly, the process of developing infrastructure in the suburbs is also far from straightforward. While Toronto’s long term network vision projects a cycling facility on nearly every arterial road in the city, the critical question is which improvements make it into the near-term implementation program. Understandably, pragmatic political and budgetary considerations often take precedence in these planning decisions – but equity considerations are making an impact.

However, as accessibility analyses indicate, simply providing the same infrastructure everywhere does not guarantee a similar ‘level of service’. Accordingly, equitable infrastructure provision is best understood as not exclusively or even primarily a matter of distribution, but rather of the type and configuration of infrastructures in relation to a particular socio-spatial context – raising complex questions of how and where to (re)configure infrastructure.

Figure 3. Map of cycling trip completion potential in Toronto as developed by Tabascio et al. (2023).

Geographical differences and spatial strategies

In continually adapting delivery mechanisms and political strategies to resolve practical problems and situations (c.f. Wilson & Mitra, 2020), Toronto’s cycling planners are often highly aware of the difficulties and opportunities offered by the city’s divergent urban forms. For instance, suburban arterials are understood to require different design approaches than downtown streets. With less constraints in the right-of-way, but higher traffic volumes and speeds in the roadway, it is often more effective and politically expedient to place cycling infrastructure along green verges or upgrade sidewalks to high-quality multi-use paths. Equally, Bike Share Toronto’s equity-driven city-wide expansion has also involved adjusting the distances between docking stations, with those in suburban wards often twice as far apart as in central Toronto. At transit stations such as Finch West, bike sharing is being complemented with a protected bicycle parking garage –an experiment in intermodal integration that will require improvements to the cumbersome and expensive access system to achieve its full potential.

As Trudy Ledsham and colleagues (2022, p. 3) have underlined, the “urban form in automotive suburbs may simply require different planning approaches than downtown cores.” This includes attending to the different practices and purposes of cycling in the suburbs. For instance, recognizing that the uptake of cycling for recreation can increase the likelihood of cycling for transport can inform a suburban strategy that expands and improves the recreational cycling network in tandem with utilitarian infrastructure. Emphasizing the need to consider the broader social determinants of cycling, suburban cycling advocates have developed community programming in the form of ‘bike hubs’ (Ledsham & Verlinden, 2019). By shifting the focus from physical infrastructure to the broader social determinants of cycling, projects in communities such as Southwest Scarborough are working to strengthen local cycling cultures, helping build support for the expansion of physical infrastructure.

From equal distribution to differential strategy

As Toronto moves towards a city-wide cycling network and equity criteria become institutionalized, the assumptions that shape infrastructure provision warrant scrutiny. In this blog, I have argued that equity analyses and policies would benefit from a geographically differentiated perspective that reveals how the impacts and function of cycling infrastructures vary according to socio-spatial context.

Comprehensively addressing demographic inequities, and the barriers to cycling in the suburbs more generally, will involve the piloting of new design configurations, supporting and empowering local cycling cultures, and the adaptation of infrastructural solutions to local mobility needs. As this blog has shown, these kinds of experiments and initiatives are already happening, and their outcomes will shape Toronto’s future as a cycling city. If we hope to harness and contribute to these processes, we’ll have to put aside the ‘view from the map’ – instead, why not take a ride through the suburbs?

For further information, consider the following lectures:

- Toronto cycling planner Kanchan Maharaj presenting on equity planning for active transportation in Toronto: https://youtu.be/X3RswCcfLYw?si=K83vS_b0KVHvZow2

- The author presenting on cycling networks and mobility justice in Manchester, Mexico City, and Toronto: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MVC8PW4X1BY

References

Allen, J., & Farber, S. (2021). Suburbanization of Transport Poverty. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1859981

Ledsham, T., & Verlinden, Y. (2019). Building Bike Culture Beyond Downtown: A guide to suburban community bike hubs. The Centre for Active Transportation at Clean Air Partnership. https://www.tcat.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Building-Bike-Culture-Beyond-Downtown-Report-Web-Version-compressed.pdf

Ledsham, T., Zhang, Y., Farber, S., & Hess, P. (2022). Beyond downtown: Factors influencing utilitarian and recreational cycling in a low-income suburb. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2022.2091496

Mitra, R., Khachatryan, A., & Hess, P. M. (2021). Do new urban and suburban cycling facilities encourage more bicycling? Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 97, 102915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2021.102915

Tabascio, A., Tiznado-Aitken, I., Harris, D., & Farber, S. (2023). Assessing the potential of cycling growth in Toronto, Canada. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 17(12), 1370–1383. https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2023.2196264

Wilson, A., & Mitra, R. (2020). Implementing cycling infrastructure in a politicized space: Lessons from Toronto, Canada. Journal of Transport Geography, 86, 102760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102760

Disclaimer: the research described in this piece was not funded by or conducted as part of Mobilizing Justice. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of Mobilizing Justice.

You may also like

The Different Price Tags of Access: Transit, Housing Affordability and Demographics

The Different Price Tags of Access: Transit, Housing Affordability and Demographics

Introduction Building a new transit system? Great for commuters. Even better for housing prices. When cities build transit, nearby land and housing prices often shoot… Read More

Developing Standards for Equity in Transportation Planning and Policy

Developing Standards for Equity in Transportation Planning and Policy

program at McMaster University. I began my PhD in September 2023 and have been part of the PhD MJ Researchers team since then. In a… Read More

Making Space for Grief: Innovate Approaches to Knowledge Mobilization Through Art, Placemaking, and Cross-Sector Dialogue

Making Space for Grief: Innovate Approaches to Knowledge Mobilization Through Art, Placemaking, and Cross-Sector Dialogue

Grief—often defined as the process of coping with loss—ebbs and flows throughout our lives. Despite its universality, this deeply human experience is often constrained by… Read More