Evaluating transport poverty and the risk of social exclusion in Canada

There is no precise definition of transport poverty, not in academic circles nor public administration, but in general terms, it is understood as the inability to access essential services or work due to unavailable or unaffordable transport provision (Luz & Portugal, 2022). This inability can have many different faces:

• a physically disabled person unable to use public transport due to urban design barriers or bus/metro units that are not adapted to their needs;

• people from vulnerable communities who live too far from transport stations that can connect them to services such as schools or hospitals;

• elderly citizens who cannot walk because they live in neighbourhoods with narrow or inexistent sidewalks;

• low-income parents unable to afford everyday, twice-a-day transport rides to reach their jobs;

• or people from immigrant communities who spend several hours travelling for work and back.

All these scenarios show how a citizen who already is in a vulnerable situation due to age, income, gender, race, immigration status, single parenthood, among other factors, can deepen its vulnerability by not having adequate access to transport services, whether because of time, money, distance, or physical barrier constraints. Hence, Lucas et al. (2016) define that an individual can be transport-poor if at least one of these conditions apply:

• there are no transport options available fitted to their physical condition and capabilities

• existing transport options do not reach destinations where they can fulfil daily activity needs

• the amount spent on transport leaves the household with a residual income below the official poverty line

• the individual needs to spend an excessive amount of time travelling

• travel conditions are dangerous, unsafe or unhealthy

The interplay between socio-economic and/or socio-demographic vulnerability and transport inaccessibility often leads to social exclusion.

Social exclusion is a complex concept, but in general, an individual can be considered socially excluded if they cannot participate in the activities that a citizen usually participates in, for reasons beyond their control (Luz & Portugal, 2022). The lack of participation comes from the inability to access life opportunities, social networks, political participation, and decision-making spaces (Lucas, 2012). It is important to note that social exclusion is often related to income, but not exclusively. This means that a person can lack economic resources but not be socially excluded from society and vice-versa. Putting it simply, if a person lacks economic resources but lives in areas where they can easily and rapidly reach (for example, by a quick bus ride) adequate employment centers and services like schools, recreation, groceries, etc., this person is more able to overcome their economic constraints with time, by having access to opportunities. In this sense, transport can be seen as a ‘bridge’ helping narrow or close the gap between economic constraints and exclusion. For this work we are interested in Transport-Related Social Exclusion, a particular type under the social exclusion umbrella that is produced when a person suffers from vulnerability in any of its socio-economic factors (race, age, income, etc.) and at the same time has no access to transport connections (whether it is by public transit, pedestrian infrastructure, private roads or multimodally), and therefore is physically and temporally isolated from opportunities due to transport factors.

In this light, understanding where and how a lack of resources and transport provision take place in cities is a prime need for transportation planning, aiming to build more equitable settlements by using transportation to combat poverty. It is necessary, therefore, to develop tools that allow locating and analyzing these phenomena to help policy makers develop strategies to prevent social exclusion.

A study made in the eight most populous metropolitan Canadian cities showed that Calgary, Edmonton, and Toronto have particularly large counts of low-income, unemployed, and recent immigrants in areas of low transit accessibility relative to their totals, while in Quebec City, Winnipeg, and Ottawa, relatively fewer vulnerable populations are living in areas with low transit accessibility (Allen & Farber, 2019), showing a need for addressing accessibility in Canadian cities. Research on transport poverty often is mainly conducted in metropolitan or urban areas, frequently disregarding smaller towns and rural areas, and, in general terms, disregarding the distribution of resources affecting these populations. Thus, Mobilizing Justice Partnership is developing an index for measuring and locating the risk of transport-related social exclusion for Canada at the national level.

Given the multidimensional, complex nature of assessing transport-related social exclusion, the development of this index contemplates a socio-economic component with multiple variables using census data, in four main topics: Households and Dwellings (household overcrowding and ownership, people living alone, etc.), Material Resources (income, education status, government aid, etc.), Age and Labour Force (age of population, dependency rate, etc.), Immigration and Visible Minorities (recent immigrants and self identified minorities) (Matheson FI et al., 2021). The transport component is measured by a group of carefully modelled accessibility measures – how easy is it to access key locations – by different travel modes (buses, walking, cycling, etc.), provided by StatsCan.

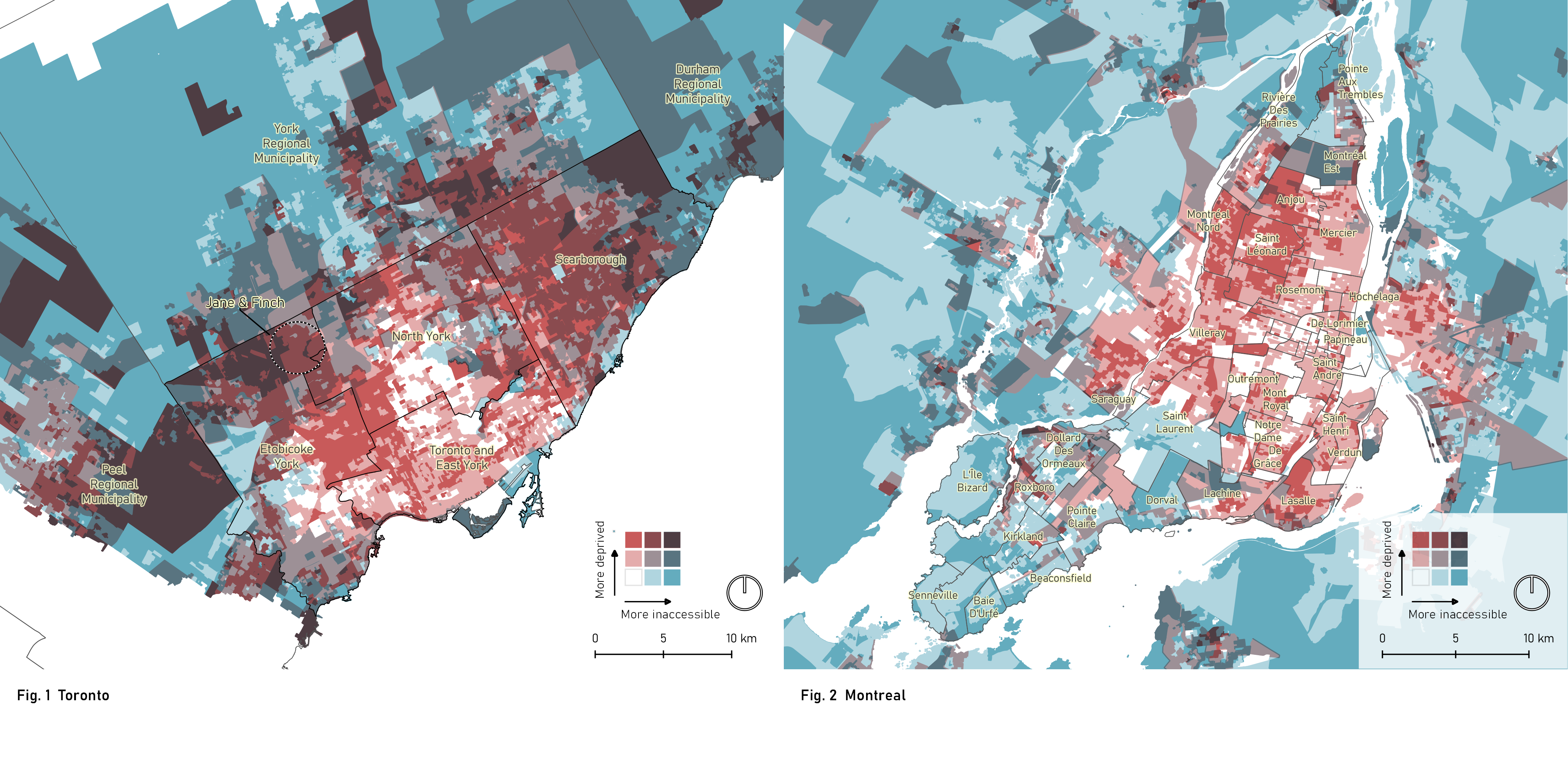

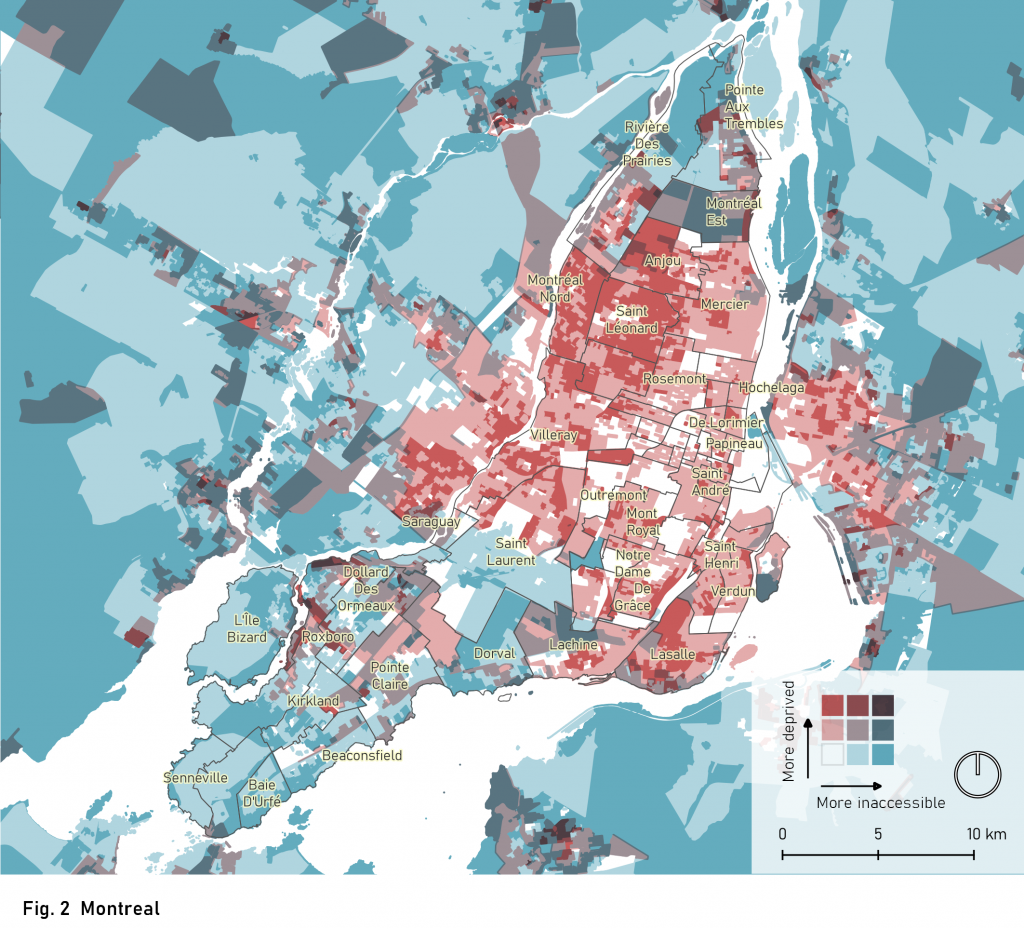

Preliminary results show that both lower socio-economic conditions and lower access by transport are found in the northwest of the Greater Toronto Area, in the neighbourhood of Jane and Finch/University Heights, a zone known for its socio-economic deprivation (Figure 1). By lacking transport access, this neighbourhood is far from important urban services and from participating in the civic life and decision-making spaces of the city that could help its inhabitants to overcome some of their constraints. The lack of accessibility and poor socio-economic conditions can also be seen in Scarborough (Figure 1).

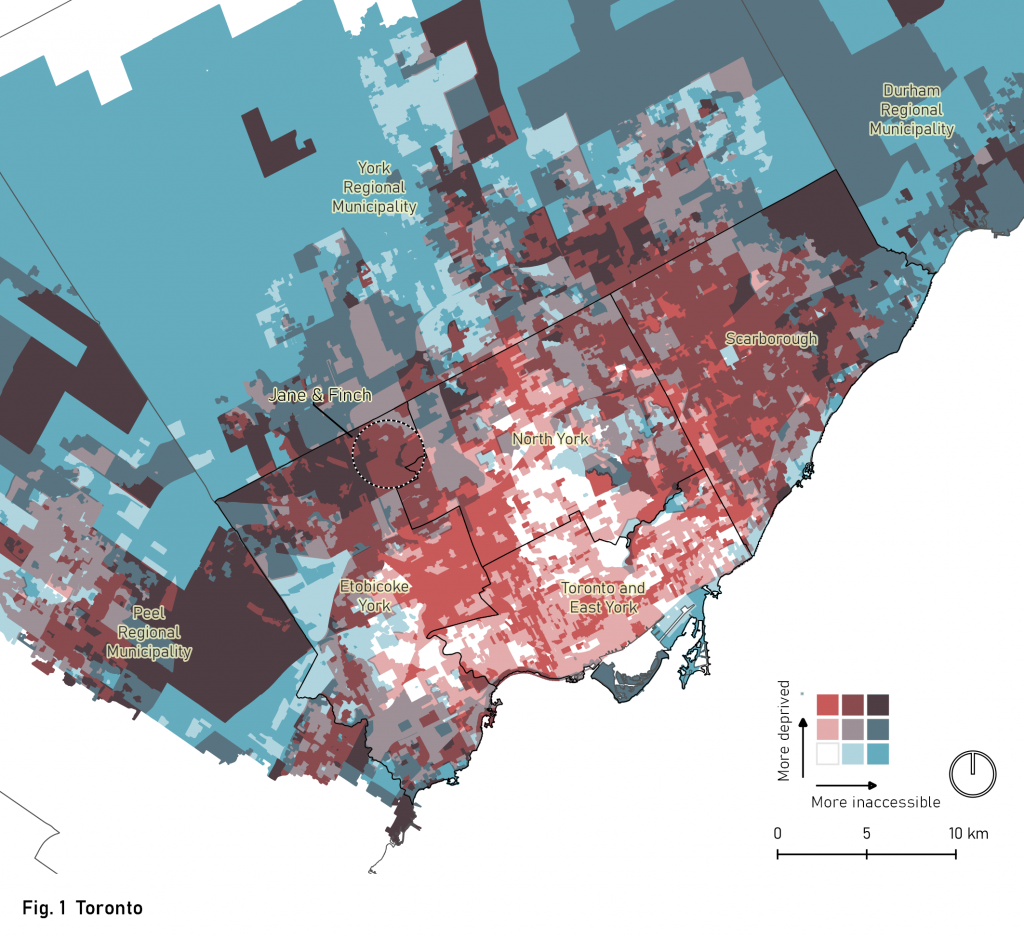

In the island of Montreal, both types of deprivation coincide at some parts of Pointe-Aux-Trembles and the south of Riviére-des-Prairies, where there are known social housing projects. In contrast, Montreal Nord, a well-known socio-economically deprived neighbourhood, has better transport accessibility, and therefore more connections to services (Figure 2). Although the index is still under development, it already shows its potential for helping prioritize transport investment where it is needed the most.

Currently we are working on refining the index, and results will come soon. Future research can focus on automated or semi-automated updates of the index when new census information is collected, on the inclusion of new dimensions of poverty (such as time poverty), and on regional dynamic systems of visualization. Additionally, the index should be socialized among public policy practitioners as a tool for informed decision-making.

References

Allen, J., & Farber, S. (2019, 2019/02/01/). Sizing up transport poverty: A national scale accounting of low-income households suffering from inaccessibility in Canada, and what to do about it. Transport Policy, 74, 214-223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2018.11.018

Lucas, K. (2012). Transport and social exclusion, Where are we now? In J. G. Urry, Margaret (Ed.), Mobilities (pp. 207-222). Routledge. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84900047232&partnerID=MN8TOARS

Lucas, K., Mattioli, G., Verlinghieri, E., & Guzman, A. (2016). Transport poverty and its adverse social consequences. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Transport, 169(6), 353-365. https://doi.org/10.1680/jtran.15.00073

Luz, G., & Portugal, L. (2022, 2022/07/04). Understanding transport-related social exclusion through the lens of capabilities approach. Transport Reviews, 42(4), 503-525. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.2005183

Matheson FI, Smith KL, Moloney G, & JR, D. (2021). 2016 Canadian marginalization index: user guide.

You may also like

Moving towards cycling equity in Toronto: infrastructures, social contexts, and spatial difference

Moving towards cycling equity in Toronto: infrastructures, social contexts, and spatial difference

Thomas van Laake, doctoral researcher at the University of Manchester Introduction In recent years, equity and justice have become central issues in bicycle planning and… Read More

Mobilizing for transportation workers: First steps towards a more just vehicle-for-hire industry in Toronto

Mobilizing for transportation workers: First steps towards a more just vehicle-for-hire industry in Toronto

by Thorben Wieditz, Director of Metstrat Digital platforms are reshaping how we work, live, and get around. The rise of the… Read More

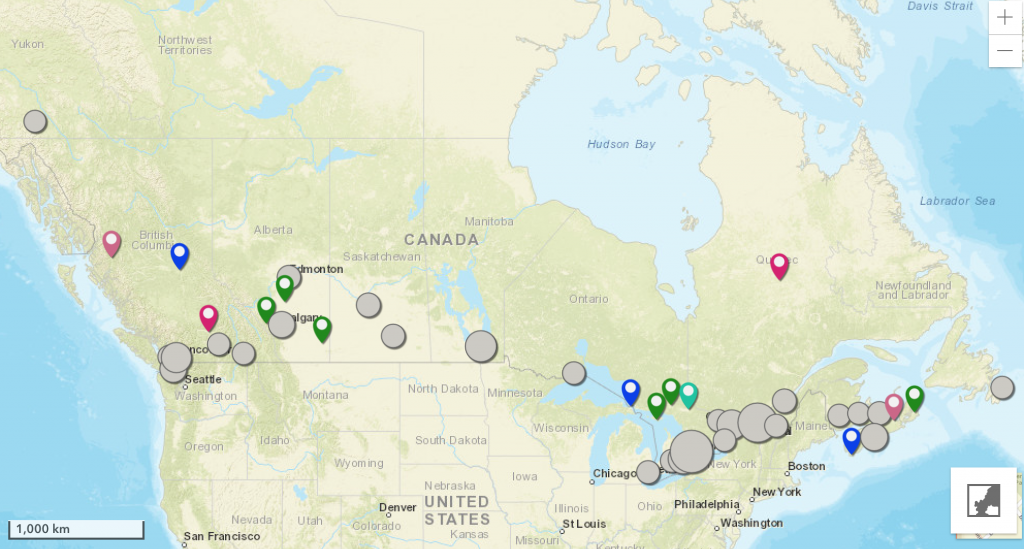

New Interactive Map and Updated Catalogue of Community Initiatives Addressing Transport Poverty Provides Valuable Repository of Local Knowledge for Mobilizing Justice Researchers and Partners

New Interactive Map and Updated Catalogue of Community Initiatives Addressing Transport Poverty Provides Valuable Repository of Local Knowledge for Mobilizing Justice Researchers and Partners

Nancy Smith Lea is the Community Co-Lead of the Mobilizing Justice Transportation Modes Thematic Working Group and a Senior Advisor at The Centre for Active… Read More