Lived Experiences of Transport Poverty in a Montreal Suburb: A Case Study of Saint-Jean-Sur-Richelieu

Rosalie is a master’s student studying Urban Planning at McGill University. Her work focuses on public transit and transportation equity. In this blog, she investigates lived experiences of transport poverty in her hometown, Saint-Jean-Sur-Richelieu.

For my undergraduate honours thesis in geography and urban studies, I focused on the impacts of suburban transport poverty. Transport poverty can be succinctly described as “the compounded lack of ability to travel to important destinations and activities” (Allen & Farber, 2019, p.3) that can result from a combination of transport disadvantage and socio-economic disadvantage. Since transport poverty is complex, with no clear definition, it can also include spending an unreasonable amount of one’s income on transportation (Currie & Delbosc, 2011). It also encompasses several factors, such as mobility poverty, accessibility poverty, transport affordability, and exposure to transport externalities (Lucas et al., 2016).

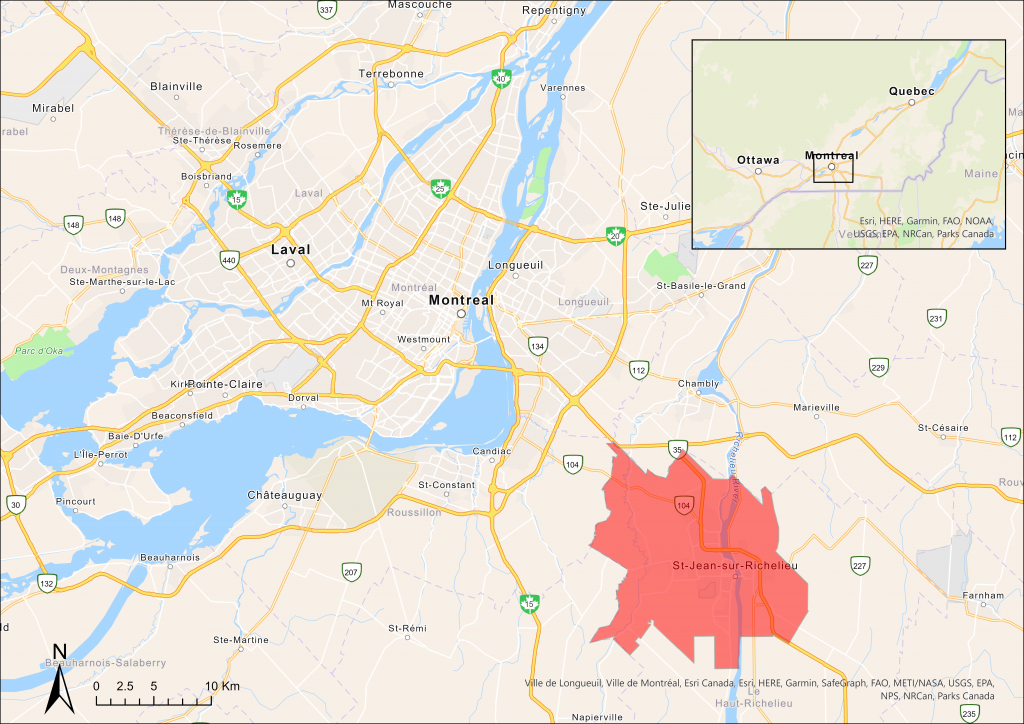

While my courses have touched upon transportation in major cities, I was interested in investigating the effects of transportation on people’s lives in suburbs, which are often car-dominated and characterized by low density, poor walkability, and lower public transit services. Combined with growing suburban poverty, suburbs are increasingly vulnerable to transport poverty, especially for those without cars (Allen & Farber, 2019, 2021). Thus, I conducted a case study of lived experiences of transport poverty in my hometown of Saint-Jean-Sur-Richelieu, located on the south shore of Montreal (Figure 1), where typical streetscapes and built form privilege car movement (Figure 2) and 85% of commuters drive to work according to the 2016 Census.

Map 1. Location of Saint-Jean-Sur-Richelieu

Figure 1. Typical Streetscape in Saint-Jean-Sur-Richelieu

To investigate lived experiences of transport poverty, my research aimed to answer three research questions:

1. What are the consequences of living in transport poverty on people’s daily lives?

2. What are the travel behaviours, if any, used to cope with transport poverty?

3. Does transport poverty affect social exclusions and well-being? If so, in what ways?

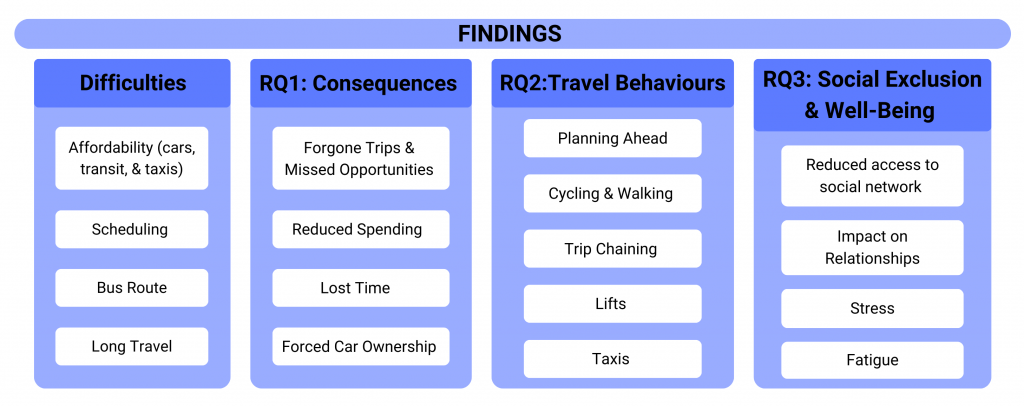

Quantitative research has already been conducted to assess the consequences and prevalence of transport poverty. However, fewer studies have explored the qualitative side of transport poverty. I conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews (n=9) accompanied by travel diaries for half of the participants (n=4) to capture the lived experiences of transport poverty. I recruited participants who did not have access to adequate and affordable transportation, including people with and without cars. I conducted all the interviews in French and then conducted a thematic analysis of my interview transcripts. The key themes found in this research are summarized in the table below.

Table 1. Key Themes

Transport difficulties

Before I started analyzing the impacts of transportation poverty on the participants, I first looked at what difficulties were reoccurring in my sample to better understand transport poverty in Saint-Jean-Sur-Richelieu. The most common transportation challenge was affordability, whether the cost of cars, transit, or taxis. This was a common issue both among students and workers. Martine (all names are pseudonyms), a 46-year-old unemployed woman, said, “I don’t have any numbers to tell you how much of an impact it has, but I would say that between my car and everything else, it costs me more than my mortgage.” Scheduling was also a significant obstacle to mobility, with the bus schedule not meeting their transport needs. Multiple participants reported being unable to go to places later in the evenings because the buses stopped running. The frequency of buses, which was for some participants every hour or two, also severely limited and complicated their mobility. Excessive travel times also impeded accessibility for some, especially when accessing destinations outside the city.

Consequences of transport poverty

The most significant consequence of transport poverty among participants were forgone trips and missed opportunities, with the lack of transit options discouraging trip-making. All participants reported missing opportunities or trips, such as social events, essential travel for groceries, employment opportunities, and school. Martine experienced such high difficulties that she could not even get proper groceries, “I will be out of something. I’ll be out of bread, I’ll be out of this, out of that, and I won’t go”. Moreover, long travel times impacted their rest time, resulting in a lack of sleep or reduced time for cooking or spending time with family.

Not only does transport poverty impact one’s income through missed employment opportunities or work hours, but it also reduces one’s remaining budget because of the high costs. Many participants had to cut costs elsewhere, often in groceries or activities; some even reported working more to pay their bus fares. Denis, a 38-year-old warehouse worker, explained, “… if I don’t look at my [budget], I’m in trouble. It has happened that I couldn’t go to work for two days. No money [so] I don’t work I just wait for the time to pass.” Further in his interview, Denis also talked about his salary not keeping up with inflation and having to cut costs at the grocery store.

Forced car ownership is often included in the definition of transport poverty, yet I found that many participants were about to be forced car owners due to transport poverty. While most participants did not own cars, many thought it was challenging to be mobile and live in Saint-Jean-Sur-Richelieu without owning a car, reflecting the car-dominated landscapes of suburbs. Many were at their limit and were about to purchase a car for more freedom and convenience despite the high cost. Mathieu, a 23-year-old student, said, “Now I’ve started working again to be able to afford a car for this summer because I’ve got two years left [of school]. I don’t think I could do this for two years.”

Travel Behaviours

Many participants had to resort to planning ahead as a coping mechanism to do as much as their daily activities while living with transport poverty. Participants often changed their plans to have better transit options or plan around transit by ensuring they had some other means available. Cycling and walking were also used when no other mode was available or affordable. While active transportation is considered desirable because of its numerous health and environmental benefits, participants had to walk or cycle in unwelcoming environments over very long distances because they had no other options available. Denis said, “I take my bike, it’s the only thing I have to get around that doesn’t cost a lot,” and “I don’t have the money to pay the $4.25 to take the bus because, by the way, it’s $4.25 [so] often I have to get around by bike”. Trip chaining was used to reduce the number of trips taken to maximize time and cost. Asking for lifts from friends and family was often used to deal with the insufficient bus schedule and long delays. Taxis were used in similar situations but as the last resort option because of their high cost.

Social Exclusion and Well-Being

Given the significant difficulties and consequences associated with transport poverty, I also investigated the impact on people’s social networks and well-being. Many participants, especially students, had difficulties maintaining relationships with friends and family because of their reduced mobility and time lost on transportation. Amanda, an 18-year-old student, said, “…it’s kind of difficult to maintain friendships, like keeping a relationship with someone. It’s easy, let’s say, to keep a friendship with someone around here because I can see them more often since I can walk or stuff like that, but with friends in the city, it’s more difficult to maintain a connection”. One participant even described his transport difficulties, making relationships sometimes uncomfortable because he needed to ask for lifts.

The main impacts on well-being among the participants were stress and fatigue. Many described their transportation as a major source of stress, especially with delays. In contrast, others, mainly working adults, described being able to relax once on the bus even if the scheduling brought them significant frustrations. Many participants, especially students, lacked sleep because they had to wake up exceedingly early to catch the bus. Antoine, a 22-year-old, even cited his stress and lack of sleep as a primary reason he left school “It was one of the major reasons why I dropped out of school at the time because it was…I just wasn’t sleeping. I just didn’t have any sleep, it, it just, it wasn’t working […] every day, I was stressed about the bus because it was always late.”

Conclusion

These findings shed light on the important impacts of transportation and on a topic that needs to be examined or discussed more in the suburbs. While most of the trips in this suburb are made by cars, this research has shown the importance of not neglecting those who are more vulnerable, such as people with low incomes and students who often do not have the means to afford cars that would provide them with the mobility necessary for their daily lives. While more research is needed, this should be considered in local governance and transit agencies that hold a lot of power and potential for change that could drastically improve the lives and well-being of residents. Offering longer operating hours, a more frequent schedule, expanding routes to lower serviced areas, and, importantly, lowering the cost of fares could go a long way to reducing transport poverty in Saint-Jean-Sur-Richelieu and potentially in other similar suburbs.

References

Allen, J., & Farber, S. (2019). Sizing up transport poverty: A national scale accounting of low-income households suffering from inaccessibility in Canada, and what to do about it. Transport Policy, 74, 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2018.11.018

Allen, J., & Farber, S. (2021). Suburbanization of Transport Poverty. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 111(6), 1833–1850. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1859981

Currie, G., & Delbosc, A. (2011). Transport Disadvantage: A Review. In G. Currie (Ed.), New perspectives and methods in transport and social exclusion research (pp. 15–26). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Lucas, K., Mattioli, G., Verlinghieri, E., & Guzman, A. (2016). Transport poverty and its adverse social consequences. Transport, 169. https://doi.org/10.1680/jtran.15.00073

Statistics Canada. (2016). 2016 Census Profiles/Profile of Census Disseminations Areas. CHASS Data Center.

You may also like

The Different Price Tags of Access: Transit, Housing Affordability and Demographics

The Different Price Tags of Access: Transit, Housing Affordability and Demographics

Introduction Building a new transit system? Great for commuters. Even better for housing prices. When cities build transit, nearby land and housing prices often shoot… Read More

Developing Standards for Equity in Transportation Planning and Policy

Developing Standards for Equity in Transportation Planning and Policy

program at McMaster University. I began my PhD in September 2023 and have been part of the PhD MJ Researchers team since then. In a… Read More

Making Space for Grief: Innovate Approaches to Knowledge Mobilization Through Art, Placemaking, and Cross-Sector Dialogue

Making Space for Grief: Innovate Approaches to Knowledge Mobilization Through Art, Placemaking, and Cross-Sector Dialogue

Grief—often defined as the process of coping with loss—ebbs and flows throughout our lives. Despite its universality, this deeply human experience is often constrained by… Read More